After the start of the Russian-Ukrainian war on February 24, 2022, a discussion arose in Estonian society about the removal of Soviet-era monuments.

To map these monuments, a working group was formed under the Republic of Estonia Government Office in the summer of 2022. This group developed solutions for removing the monuments and for replacing Soviet-era monuments on the mass graves of Red Army soldiers with neutral ones. On November 23, 2022, the working group presented its findings, having mapped a total of 321 Soviet war monuments. Most of these monuments were erected on the mass graves of Red Army soldiers who fell primarily in World War II. (1)

The Government Office handed over the collected materials on Soviet war monuments to the Estonian War Museum at the beginning of 2023. Based on this, the database “Soviet War Monuments and War Graves in Estonia 1944–1991”, compiled by the author of this article, was made public in the spring of 2025. (2)

The Erection of Soviet War Monuments in Estonia, 1940–1941, 1944–1991

Before examining the database “Soviet war monuments and war graves in Estonia in 1944–1991,” we should briefly look at how the Soviet occupation authorities established these monuments and war graves in Estonia.

In the summer of 1940, when the Republic of Estonia was occupied by the Soviet Union, the destruction of the Estonian state apparatus and the repression of the political elite began. Additionally, monuments erected across Estonia to honor those who fell in the Estonian War of Independence were removed, as these memorials did not align with the Soviet historical narrative, which portrayed the conflict as a class and civil war. The Soviet occupation authorities continued to destroy these monuments the autumn of 1944, when Red Army occupied Estonia again. (3)

The first Soviet war monuments were erected during the first Soviet occupation (1940–1941) year. One such monument was built in 1940 at Maarjamäe in Tallinn. It marked the grave of sailors from the Soviet Baltic Fleet destroyers Spartak and Avtroil, who were shot in the Naissaar prison camp in 1919 during the Estonian War of Independence. This monument was destroyed during the German occupation (1941-1944) period, because a German military cemetery was established nearby. (4)

The mass erection of Soviet war monuments began after the Red Army’s second occupation of Estonia in the autumn of 1944. At this time, the burial of fallen Red Army soldiers and the erection of temporary grave markers also began.

For the 10th anniversary of the Estonian SSR in 1950, architect Alar Kotli developed standard monument designs that were subsequently erected on the mass graves of Red Army soldiers. (5) A new wave of erecting Soviet war monuments began in the 1960s when, with the rise of Leonid Brezhnev to power in the Soviet Union, the celebration of the Second World War Victory Day on May 9 gained momentum. (6)

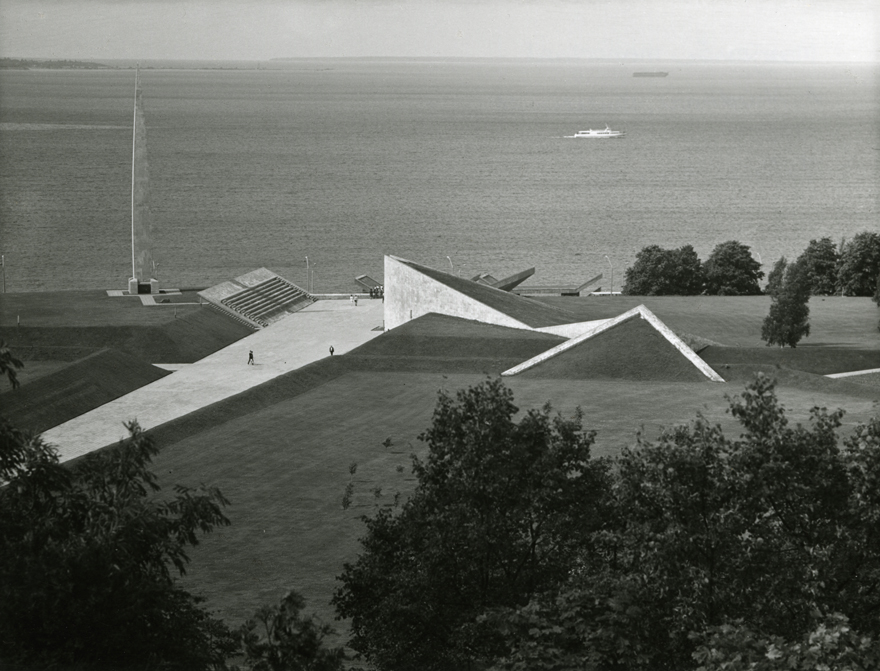

Notable monuments from this period include the memorial at Maarjamäe in Tallinn, which was dedicated to those who fought for Soviet power. The first stage of this memorial was opened in the summer of 1975, and a second stage was planned but never completed due to the restoration of Estonian independence in 1991.(7) It’s important to note that part of the Maarjamäe memorial is located on the site of a World War II-era German military cemetery.

Another major Soviet war monument from the 1960s is the Tehumardi battle monument, opened in 1967 in Saaremaa. The monument commemorates the Battle of Tehumardi, which took place in October 1944 between a retreating German battalion and advancing units of the Red Army’s 8th Estonian Rifle Corps. Besides the Tehumardi battle monument, there was also a mass grave for Red Army soldiers. In 2024, the Estonian War Museum conducted excavations at the Tehumardi mass grave, and the remains of the fallen were reburied at the Vananõmme cemetery in Saaremaa.(8)

The Database “Soviet War Monuments and War Graves in Estonia 1944 – 1991”

The Estonian War Museum received the materials compiled by the Government Office in January 2023, and the author of this article began creating the database based on this information. Additionally, 45 more Soviet war monuments were found, including some that marked Soviet war graves.

Based on the collected data, a map application was developed. For each monument, it provides historical information, whether the monument has been removed, links to additional information, and photos.

If a Soviet war monument was a marker for a mass grave of Red Army soldiers, the database contains the number of people buried there, according to the data from the military commissariats of the Estonian SSR. If excavations have taken place at the grave, the database also notes the actual number of remains found and where they were reburied. Generally, the data from the Estonian SSR Military Commissariats regarding the number of buried individuals is not accurate and is often highly inflated. However, excavations of two war graves—in the Võsu township and in Muuksi village in Kuusalu parish—have so far shown numbers that matched the commissariats’ data.

If a monument on a grave has been replaced with a neutral marker, the database includes photos of both the new neutral marker and the original Soviet-era monument.

The database is also linked to the email address monument@esm.ee, where people can submit additional or clarifying information about Soviet war monuments or war graves. In summary, people have sent additional information to this email address, and the database is being used widely. As of September 13, 2025, the database has been visited a total of 7,584 times.

The author Ranno Sõnum is a research fellow at the Estonian War Museum, magister student of history from University of Tartu.

Picture: Maarjamäe memoriaal, panoraamvaade. Arhitekt Allan Murdmaa, obelisk Mart Port; skulptor Matti Varik; reljeefid Lembit Tolli, EAM Fk 7470, Eesti Arhitektuurimuuseum SA, http://www.muis.ee/en_GB/museaalview/2637626

References:

(1) https://riigikantselei.ee/en/monuments

(2) https://esm.ee/en/war-monuments/

(3) A. Kuusik. The Destruction of Monuments from Period of Independence in the Estonian SSR. – M. Saueauk, M. Maripuu (edit). Propaganda, immigration, and monuments : perspectives on methods used to entrench Soviet power in Estonia in the 1950s–1980s. Proceeding of the Estonian of Historical Memory 3/2021. Tartu: University of Tartu Press, 2022, pp. 139 – 179.

(4) T. Hiio. The history of monuments and memorials at Maarjamäe 1940 – 1990. – M. Saueauk, M. Maripuu (edit). Propaganda, immigration, and monuments : perspectives on methods used to entrench Soviet power in Estonia in the 1950s–1980s. Proceeding of the Estonian of Historical Memory 3/2021. Tartu: University of Tartu Press, 2022, pp. 186– 190.

(5) R. Sõnum. Nõukogude sõjamonumendid Eestis 1944– 1955 [Soviet War monuments in Estonia 1944 – 1955]. Bachelor’s thesis. Tartu: University of Tartu, Institute of History and Archaeology, Department of Estonian History, 2025, pp. 12-13, 18, 27, 28

(6) M. Miil. Vaigistatud kangelased. Suure isamaasõja veteranid Nõukogude Eesti tähtpäevaajakirjanduses 1944 – 1989 [Silenced Heroes: Veterans of the Great Patriotic War in the Anniversary Journalism of Soviet Estonia from 1944 to 1989]. – T. Hiio (peatoim). Eesti sõjaajaloo aastaraamat 3 (9) 2013: 200 aastat Napoleoni sõjakäigust Venemaale ja selle mõju Läänemere maadele = Estonian Yearbook of Military History 3 (9) 2013: Napoleonic Wars and the Baltic Sea Region: 200 years since French Invasion of Russia. Viimsi – Tallinn: Eesti sõjamuuseum – kindral Laidoneri muuseum, Tallinna Ülikooli kirjastus, 2013, p. 250.

(7) T. Hiio. The history of monuments and memorials at Maarjamäe, pp. 222, 225 – 226.

(8) Database “Soviet War Monuments and War Graves in Estonia 1944–1991″, https://www.google.com/maps/d/u/0/viewer?mid=1Xfv5HMUIlTaq4bgTklQAqQ8Y_E3Y1xg&ll=58.176874360000014%2C22.253594299999993&z=18 (23.08.2025).